As a child, did you sit on your grandparents’ knee while they regaled you with stories about your family? Perhaps there was a great-grandparent who valiantly fought in a war; or maybe an uncle was the first to have a motor car in the community.

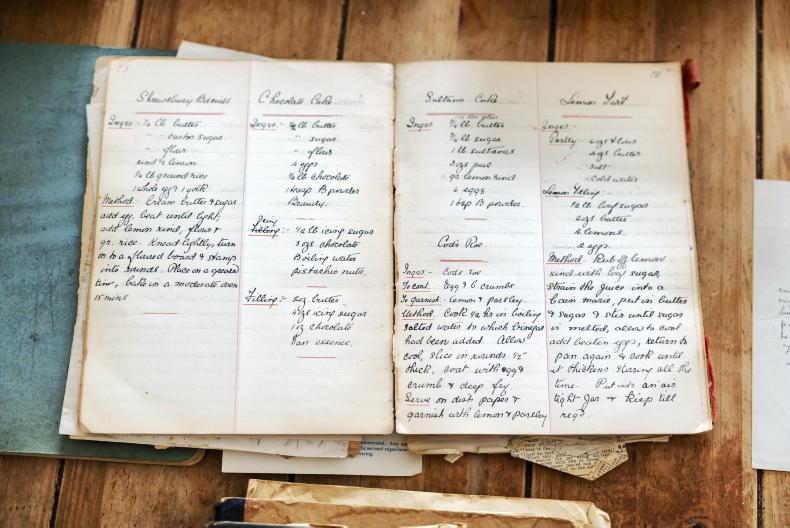

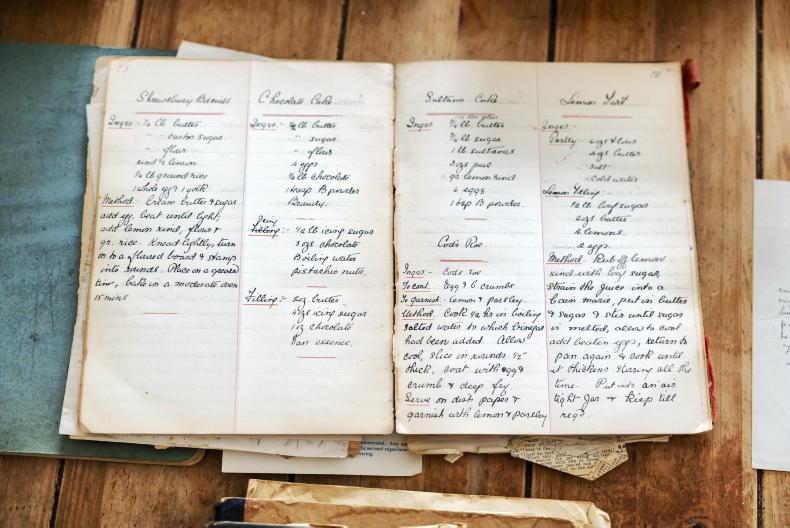

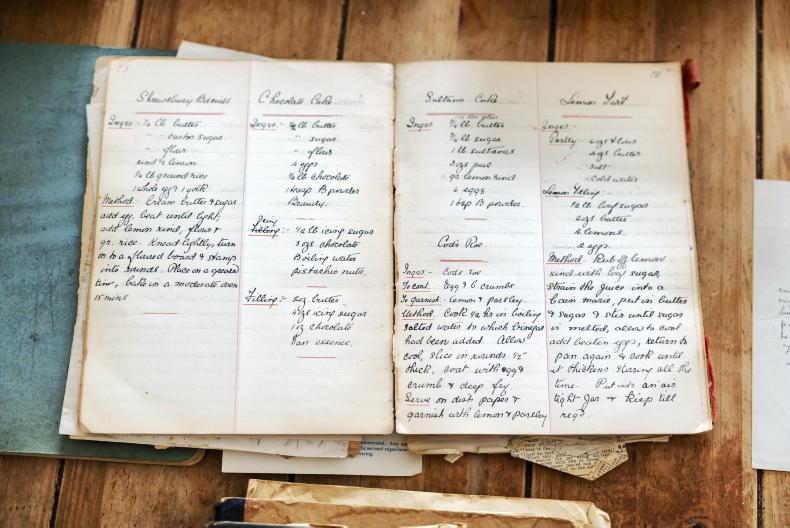

Much of our personal history is passed down orally in this way – but not all. Often, you can find family stories sitting quietly on the kitchen shelf in the form of old, handwritten recipes. Like those passed-down stories, handwritten recipes contain details of our past and provide a glimpse into the lives of those who came (and went) before us.

For generations, women have written down recipes and household tips for practical reasons – to remember how to make something, or to steal a recipe they enjoyed from a friend. They likely had no idea they were imparting a form of living history as they scribbled in their notebooks.

Irish food historians have used cookbooks and handwritten recipes from throughout the medieval and late 19th century eras to gain an understanding of not just what we were eating at a certain time in history, but, ultimately, how we were living.

When Fallon Moore was studying for a diploma in Food Culture and Irish Foodways at University College Cork (UCC), she was able to delve deep into her own family’s history and food culture. She did this by studying old recipe books, dating from the early part of the 20th century.

“These old cookbooks were stored at home, in my parents’ kitchen,” she says.

“As a child, I would leaf through them and some of these recipes were just so wild to read. [For example], there was a recipe on how to prepare calf’s head, which fascinated me.”

“The timeline of the collection is not exact, however there are certain facts we can establish,” Fallon’s research report reads. “On the first page, the author has written her name, Eileen McMahon, and as this is her maiden name, it indicates that it is pre-1922. There are newspaper clippings and notes throughout the book which carry various dates, the latest being 1963.”

“I was curious about these books and I’d always loved reading cookbooks,” Fallon tells Irish Country Living Food. “When I was doing my diploma, we had a chance to do a project on an original source. I asked if I could focus on these handwritten recipes. While researching, I was tempted to try so many of these recipes [except maybe the calf’s head]. But even with that recipe, step one was ‘remove brains’ – so with many, there was an expected level of skill involved.”

Fallon is no stranger to food culture. In Irish food circles, she is well-known as one of the main organisers of the annual Blas na h’Éireann awards. Her father, Artie, founded the awards in 2007 as a way to bring quality food awards to the island of Ireland. Now, Blas has become an annual pilgrimage for the Irish food community.

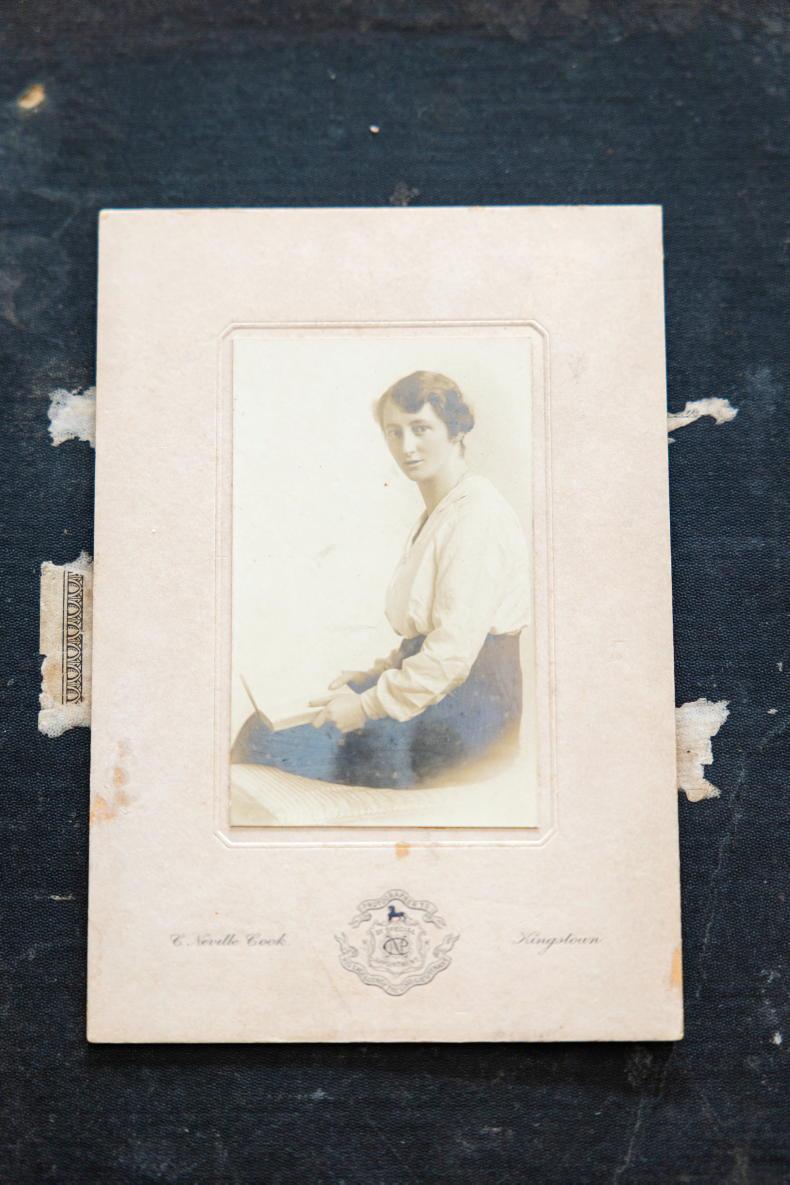

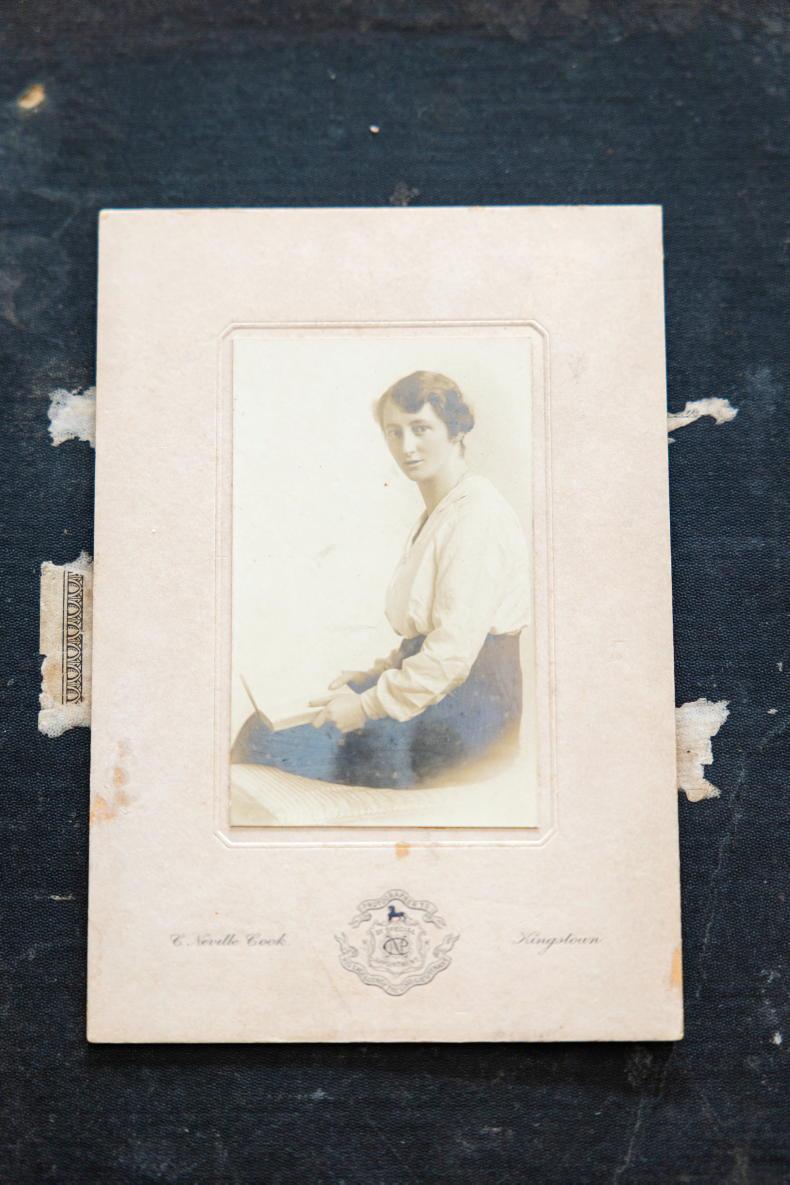

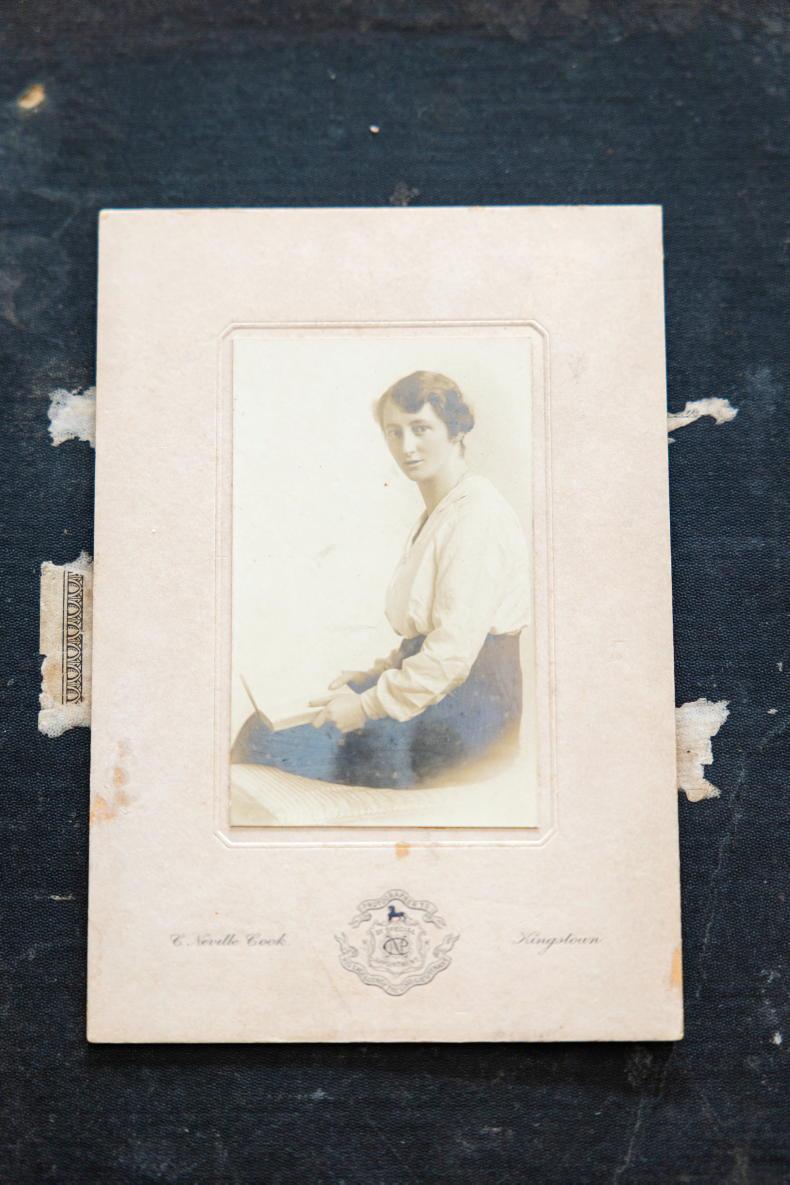

Eileen Keady was Fallon’s great-grandmother. She kept detailed recipe books with tips on household entertaining.

Culinary history

While food is very much Fallon’s life’s work, she says she learned much more than culinary history from her family’s recipes.

“The collection started with my great-grandmother, Eileen Keady, and then it went to her daughter, Margaret, who was my dad’s mother,” she says.

“There’s a collection of Eileen’s handwritten recipes, and there’s a huge amount of swapping with friends, where recipes are noted to certain people. There are recipes found on the back of shopping lists and bridge cards, and then the collection was added to by my grandmother.

Fallon Moore (pictured in her Dingle kitchen) with her great-grandmother’s egg-less almond paste tart with strawberries. \Claire Nash

“They were both domestic science teachers, and my grandmother also worked with the ESB as an instructor [when people first starting having electricity in their homes]. I have her notes from when she’d be going to houses, trying to get people to convert to electric power. They thought the farmers would be up for it, but it was actually the farmers’ wives. She was able to talk through things like freezing and preservation.”

Fallon discovered that these recipes were a beautiful example of her family’s living history; providing insight into who her grandmother and great-grandmother were. Studying also helped explain why her family eats and gathers the way they do.

“As I was researching, I was talking to my dad and his siblings,” she says. “There were things we were able to track back. Like rissoles – they would have made these to use up any leftover meat. Rissoles were a family food the siblings would all automatically think of. That was a lovely connection, knowing rissoles were something we continued to eat as children.”

Eileen Keady was Fallon’s great-grandmother. She kept detailed recipe books with tips on household entertaining.

Social affairs

The old adage tells us that history tends to repeat itself. This is why it is so important to study our past and, perhaps, re-learn some skills we have lost to modernisation. Fallon says her great-grandmother was keen on avoiding food waste.

“Eileen came from a draper’s family and her husband was secretary for the minister of social affairs,” Fallon recounts. “She was expected to keep up with society and host dinners. However, my father and his siblings all described her as ‘glamourous, but thrifty.’”

“Eileen is a bridge between the past and present,” Fallon’s research paper concludes. “The connection, for me, from the seeming distant historical collections such as the Townley Hall papers, to our own kitchen and how we live, had the most impact. Rissoles are still a regular on a Monday, macaroni is a family favourite in every one of her grandchildren’s houses, and her fudge recipe, which sits alongside notes on how to make coffee in her collection, has been made by her grandchildren [and great-grandchildren].”

Fallon’s notes on the recipe:

“This egg-less almond paste recipe is not one of Eileen Keady’s own recipes, but one of the little gems shared by her friends and tucked in between the pages of her book, which is almost 100 years old.

“This recipe is written by Mrs Seán Mac Bride. I think that this was Catalina Bulfin, wife of Seán Mac Bride, who was the son of Maud Gonne. A little historical connection.

“Our great-grandfather worked in government buildings at the same time as Seán Mac Bride, so I can only guess that a friendship was struck between the couples and recipe exchanges began.”

Makes 1kg of almond paste

Ingredients

450g caster sugar

2 tbsp water

450g ground almonds

2 tbsp rum (or any other flavouring,

like vanilla essence)

Method

1 Use a strong saucepan which will hold the heat well. Heat this saucepan over medium-low.

2 Add the caster sugar and the water. Stir this mixture constantly over the medium-low heat until the sugar has entirely dissolved.

3 Add the ground almonds and remove from the heat.

4 Stir this mixture thoroughly until a smooth, thick paste has formed and the mixture is well-heated through.

5 Add in the rum or your flavouring of choice (Fallon uses Mourne Dew’s The Pooka Hazelnut Poitín) and stir through until completely combined.

6 Store the paste in the fridge in an airtight container for 3-4 days, until ready to use.

Fallon’s suggestion

7 Fallon uses Roll It Pastry, which is Irish, for this recipe. Add a layer of strawberry jam on the base of the pastry, followed by a thick layer of the almond paste. Layer sliced, fresh strawberries over the top, brush the edges of the pastry with beaten egg, and bake in a hot 200°C oven for 25-30 minutes.

Read more

Blas na hÉireann: if you’re not in it, you can’t win it

Food News: events returning in the west

As a child, did you sit on your grandparents’ knee while they regaled you with stories about your family? Perhaps there was a great-grandparent who valiantly fought in a war; or maybe an uncle was the first to have a motor car in the community.

Much of our personal history is passed down orally in this way – but not all. Often, you can find family stories sitting quietly on the kitchen shelf in the form of old, handwritten recipes. Like those passed-down stories, handwritten recipes contain details of our past and provide a glimpse into the lives of those who came (and went) before us.

For generations, women have written down recipes and household tips for practical reasons – to remember how to make something, or to steal a recipe they enjoyed from a friend. They likely had no idea they were imparting a form of living history as they scribbled in their notebooks.

Irish food historians have used cookbooks and handwritten recipes from throughout the medieval and late 19th century eras to gain an understanding of not just what we were eating at a certain time in history, but, ultimately, how we were living.

When Fallon Moore was studying for a diploma in Food Culture and Irish Foodways at University College Cork (UCC), she was able to delve deep into her own family’s history and food culture. She did this by studying old recipe books, dating from the early part of the 20th century.

“These old cookbooks were stored at home, in my parents’ kitchen,” she says.

“As a child, I would leaf through them and some of these recipes were just so wild to read. [For example], there was a recipe on how to prepare calf’s head, which fascinated me.”

“The timeline of the collection is not exact, however there are certain facts we can establish,” Fallon’s research report reads. “On the first page, the author has written her name, Eileen McMahon, and as this is her maiden name, it indicates that it is pre-1922. There are newspaper clippings and notes throughout the book which carry various dates, the latest being 1963.”

“I was curious about these books and I’d always loved reading cookbooks,” Fallon tells Irish Country Living Food. “When I was doing my diploma, we had a chance to do a project on an original source. I asked if I could focus on these handwritten recipes. While researching, I was tempted to try so many of these recipes [except maybe the calf’s head]. But even with that recipe, step one was ‘remove brains’ – so with many, there was an expected level of skill involved.”

Fallon is no stranger to food culture. In Irish food circles, she is well-known as one of the main organisers of the annual Blas na h’Éireann awards. Her father, Artie, founded the awards in 2007 as a way to bring quality food awards to the island of Ireland. Now, Blas has become an annual pilgrimage for the Irish food community.

Eileen Keady was Fallon’s great-grandmother. She kept detailed recipe books with tips on household entertaining.

Culinary history

While food is very much Fallon’s life’s work, she says she learned much more than culinary history from her family’s recipes.

“The collection started with my great-grandmother, Eileen Keady, and then it went to her daughter, Margaret, who was my dad’s mother,” she says.

“There’s a collection of Eileen’s handwritten recipes, and there’s a huge amount of swapping with friends, where recipes are noted to certain people. There are recipes found on the back of shopping lists and bridge cards, and then the collection was added to by my grandmother.

Fallon Moore (pictured in her Dingle kitchen) with her great-grandmother’s egg-less almond paste tart with strawberries. \Claire Nash

“They were both domestic science teachers, and my grandmother also worked with the ESB as an instructor [when people first starting having electricity in their homes]. I have her notes from when she’d be going to houses, trying to get people to convert to electric power. They thought the farmers would be up for it, but it was actually the farmers’ wives. She was able to talk through things like freezing and preservation.”

Fallon discovered that these recipes were a beautiful example of her family’s living history; providing insight into who her grandmother and great-grandmother were. Studying also helped explain why her family eats and gathers the way they do.

“As I was researching, I was talking to my dad and his siblings,” she says. “There were things we were able to track back. Like rissoles – they would have made these to use up any leftover meat. Rissoles were a family food the siblings would all automatically think of. That was a lovely connection, knowing rissoles were something we continued to eat as children.”

Eileen Keady was Fallon’s great-grandmother. She kept detailed recipe books with tips on household entertaining.

Social affairs

The old adage tells us that history tends to repeat itself. This is why it is so important to study our past and, perhaps, re-learn some skills we have lost to modernisation. Fallon says her great-grandmother was keen on avoiding food waste.

“Eileen came from a draper’s family and her husband was secretary for the minister of social affairs,” Fallon recounts. “She was expected to keep up with society and host dinners. However, my father and his siblings all described her as ‘glamourous, but thrifty.’”

“Eileen is a bridge between the past and present,” Fallon’s research paper concludes. “The connection, for me, from the seeming distant historical collections such as the Townley Hall papers, to our own kitchen and how we live, had the most impact. Rissoles are still a regular on a Monday, macaroni is a family favourite in every one of her grandchildren’s houses, and her fudge recipe, which sits alongside notes on how to make coffee in her collection, has been made by her grandchildren [and great-grandchildren].”

Fallon’s notes on the recipe:

“This egg-less almond paste recipe is not one of Eileen Keady’s own recipes, but one of the little gems shared by her friends and tucked in between the pages of her book, which is almost 100 years old.

“This recipe is written by Mrs Seán Mac Bride. I think that this was Catalina Bulfin, wife of Seán Mac Bride, who was the son of Maud Gonne. A little historical connection.

“Our great-grandfather worked in government buildings at the same time as Seán Mac Bride, so I can only guess that a friendship was struck between the couples and recipe exchanges began.”

Makes 1kg of almond paste

Ingredients

450g caster sugar

2 tbsp water

450g ground almonds

2 tbsp rum (or any other flavouring,

like vanilla essence)

Method

1 Use a strong saucepan which will hold the heat well. Heat this saucepan over medium-low.

2 Add the caster sugar and the water. Stir this mixture constantly over the medium-low heat until the sugar has entirely dissolved.

3 Add the ground almonds and remove from the heat.

4 Stir this mixture thoroughly until a smooth, thick paste has formed and the mixture is well-heated through.

5 Add in the rum or your flavouring of choice (Fallon uses Mourne Dew’s The Pooka Hazelnut Poitín) and stir through until completely combined.

6 Store the paste in the fridge in an airtight container for 3-4 days, until ready to use.

Fallon’s suggestion

7 Fallon uses Roll It Pastry, which is Irish, for this recipe. Add a layer of strawberry jam on the base of the pastry, followed by a thick layer of the almond paste. Layer sliced, fresh strawberries over the top, brush the edges of the pastry with beaten egg, and bake in a hot 200°C oven for 25-30 minutes.

Read more

Blas na hÉireann: if you’re not in it, you can’t win it

Food News: events returning in the west

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: