Climate change will directly affect how Ireland’s farmers manage their land, as they have to adapt to warmer temperatures, more intense rain and more intense droughts.

However, changing weather patterns also bring with them a whole new set of disease pressures for livestock.

Warmer temperatures will see midge, mosquito and tick populations increase and some move here from mainland Europe.

Midges carry diseases to which Ireland’s cattle herds and sheep flocks are susceptible – Schmallenberg virus, bluetongue and epizootic haemorrhagic disease.

Intense droughts will bring livestock into closer contact with badgers potentially carrying TB, while wetter conditions will increase the risk of liver fluke and other diseases.

So, how long until all this comes to pass?

It’s already happening, according to Dr Damien Barrett, senior superintending veterinary inspector with the Department of Agriculture.

In recent years, liver fluke infection has increased 12-fold in certain EU member states, including Ireland. Some of this increase is connected to drug resistance among fluke, but warmer and wetter weather is helping the liver fluke’s host mud snail to thrive.

Dr Barrett, speaking on an Agricultural Science Association webinar, highlighted the increased regional spread of liver fluke disease on the island of Ireland.

Livers showing the effect of liver fluke infection. From left: a healthy liver, a liver containing acute liver fluke; a chronically infected liver and a liver badly affected on and off for a long period of time.

“It was previously a disease of the northwest and west but now it’s actually moved more and more east,” he explained.

Lamb slaughter surveys show fluke antibodies recorded in Co Kilkenny, which would never have been the case 30 years ago.

“We have seen it move towards the southeast as rainfall increases,” he said.

Liver fluke disease costs the Irish agriculture industry an estimated €90m annually, according to Animal Health Ireland. Liver fluke disease can cut meat production by up to 20% in cattle and 30% in sheep and it can reduce milk output by 8% in cows.

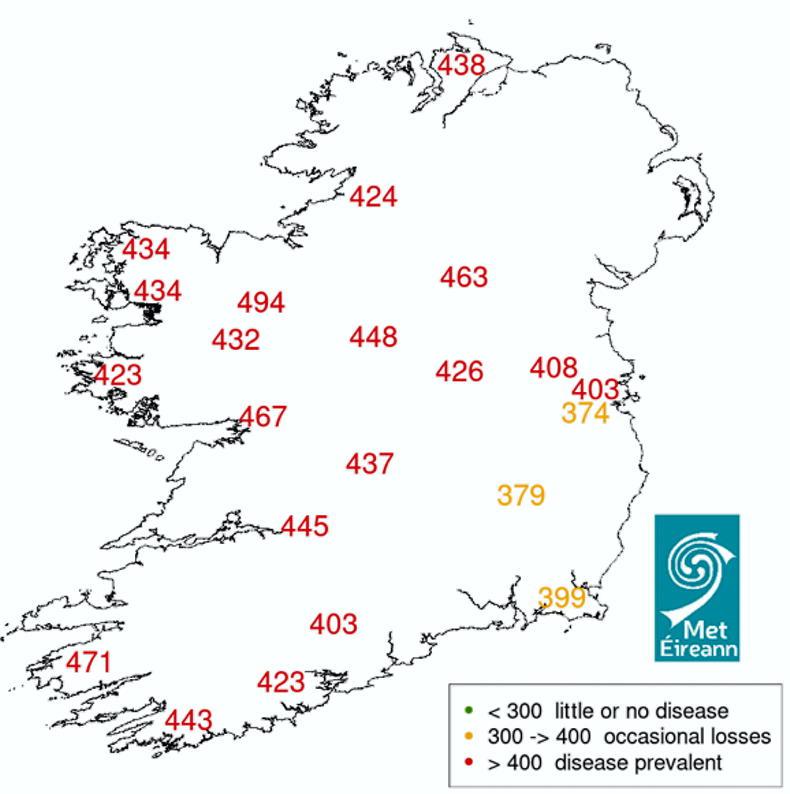

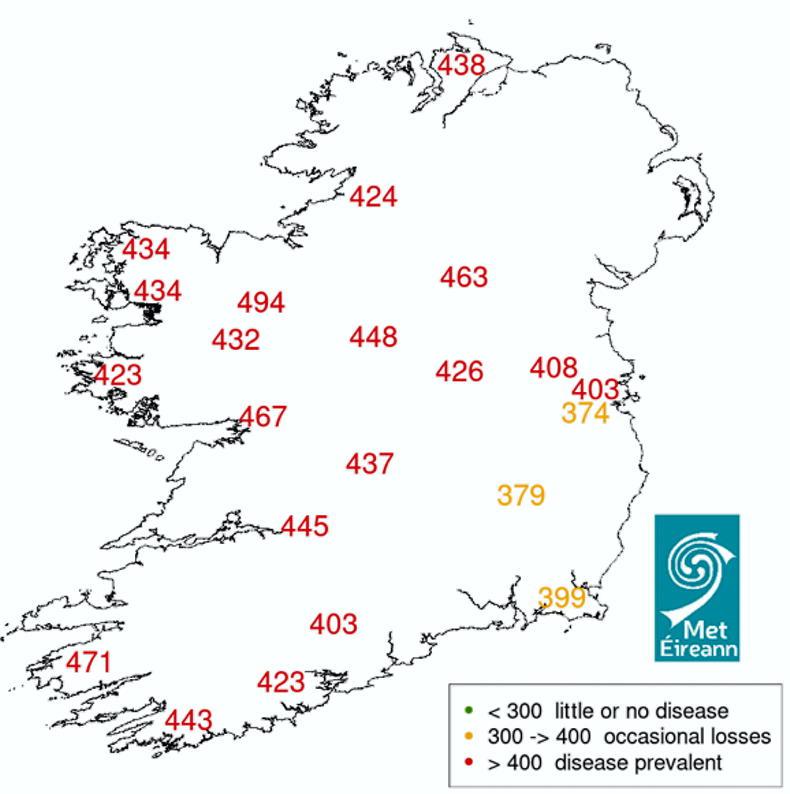

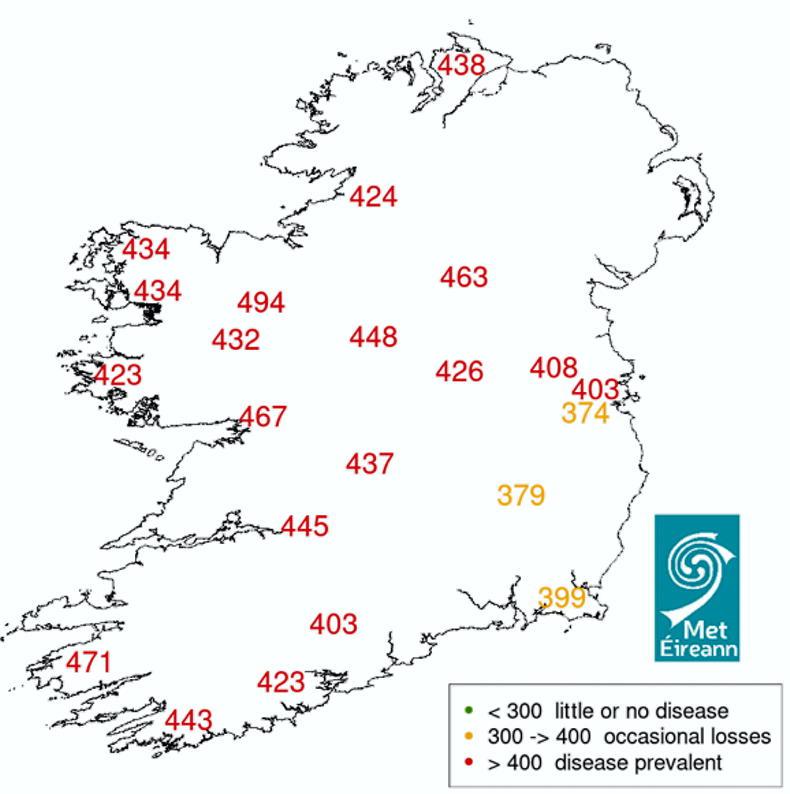

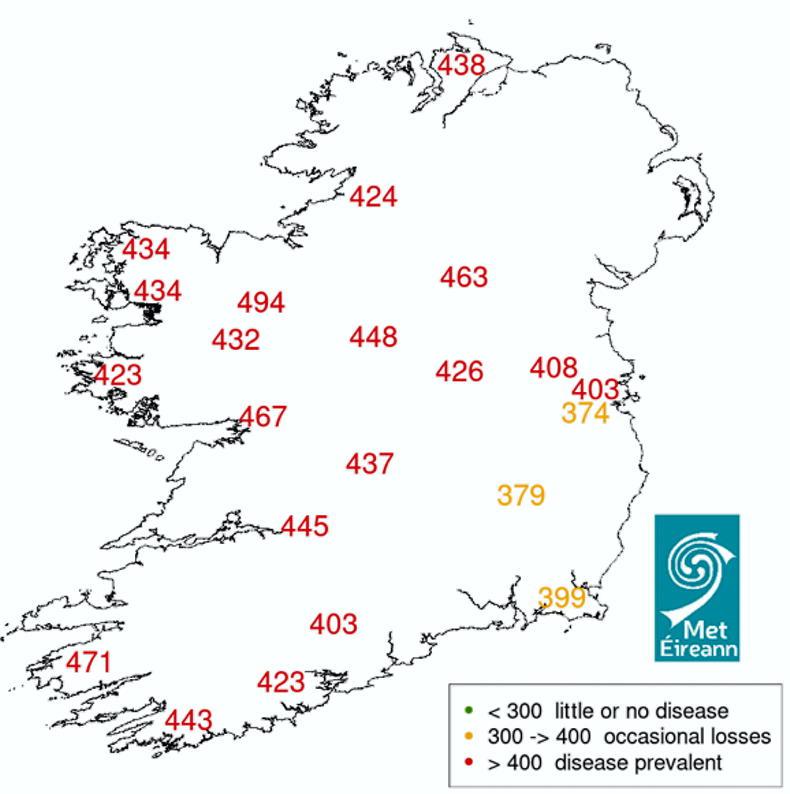

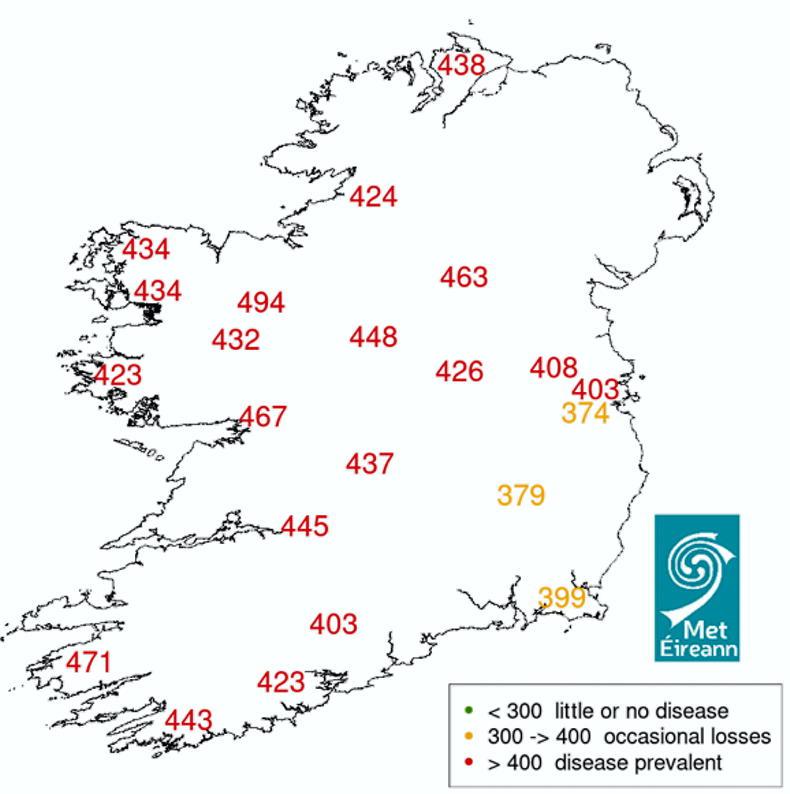

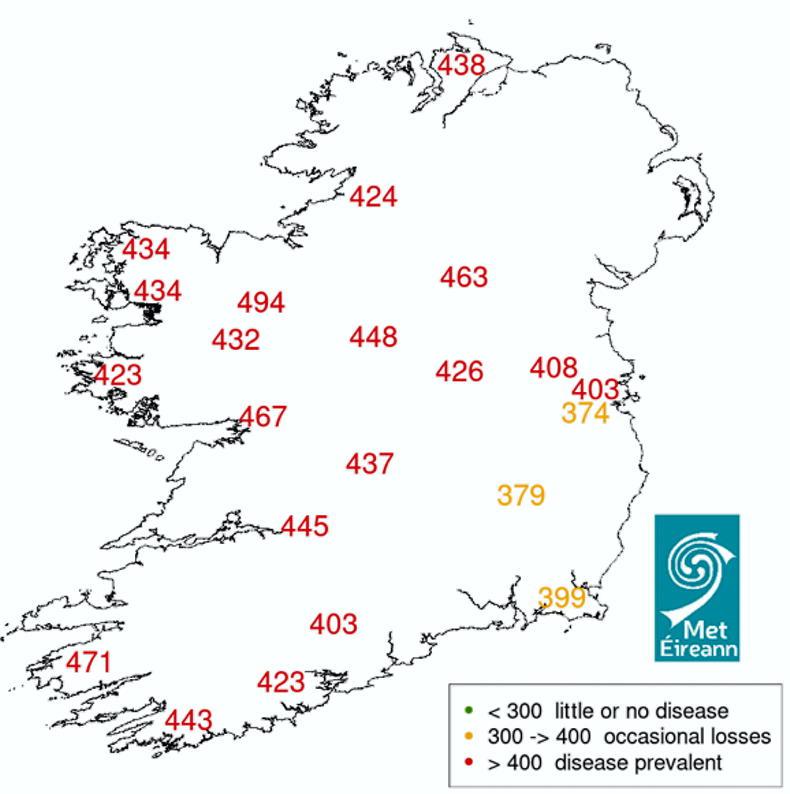

The Ollerenshaw Summer Index 2023, predicted liver fluke infection being prevalent across all areas of Ireland except south Leinster.

Until recently, rumen fluke infection was not considered to be a significant parasitic disease in cattle or sheep. However, there has been an increase in outbreaks of scour and ill-thrift due to rumen fluke in certain years.

Rumen fluke, pictured, is associated with summers and autumns with high rainfall and is in the rise in Ireland.

“We’ve seen it become more and more prevalent as rainfall increases, particularly flooding events,” explained Dr Barrett. Submergence in water is an important part of the rumen fluke life cycle, and its rising incidence is linked to high levels of rainfall and more flooding.

“[Rumen fluke], over the last 20 years, has assumed a greater importance and it has a big impact on the thrive of cattle and sheep.”

Barber’s Pole worm: fatalities on 70 farms

The parasite haemonchus contortus, also known as the Barber’s Pole worm because of its red and white appearance, was almost unknown in Ireland 30 years ago. However, it began to emerge as a problem in the early 2000s and last year it surged to cause animal deaths on at least 70 farms.

“It first emerged in the south and southeast and now it has spread across the country,” Dr Barrett said.

Warmer temperatures will see midge, mosquito and tick populations increase, potentially carrying new diseases from mainland Europe. \ Donal O'Leary

Barber’s Pole larvae require warm, moist conditions to migrate to grass, conditions which will increase as climate patterns change in Ireland. See Figure 1.

Dr Barrett highlighted a link between changing weather patterns and the sudden emergence of certain worms in livestock.

“We often see surges in lungworms and stomach worms if we have a period of low rainfall, or almost drought, followed by high rainfall,” he explained.

The Ollerenshaw Summer Index 2023, predicted liver fluke infection being prevalent across all areas of Ireland except south Leinster.

“We’ve seen that to happen over the last few years from time to time, where you get… a lack of rain for several weeks, and then the rains come and there’s a surge in grass growth and there’s a surge in lungworm larvae and stomach worms, causing scour and other problems.”

Rising temperatures increase risk from vector-borne diseases such as Schmallenberg and bluetongue viruses carried by midges, and Lyme disease, carried by ticks.

Just as human health experts are warning that mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue-fever will spread into previously unaffected parts of northern Europe, Asia, North America and Australia, animal diseases will also move to new areas. Warmer and more humid weather, with fewer frosts and a shorter cold winter, will help midges, mosquitos and ticks thrive, increasing the risk of new and existing diseases.

Schmallenberg midges carried on wind

Schmallenberg virus emerged in Germany and the Netherlands in August 2011 when farmers and vets noted cattle and sheep with fever, lack of appetite, diarrhoea and reduced milk production.

A few months later, deformed lambs and calves were born on those same farms.

The young animals had deformed limbs, spinal curvature, twisted necks, shortened lower jaws and domed skulls.

Schmallenberg quickly spread all over Europe. It was discovered in Ireland in October 2012, following the birth of a deformed calf. That year, Schmallenberg infection was confirmed in a further 48 Irish cattle herds and 39 sheep flocks, predominantly in the southeast.

“That was the first time we’ve seen midge-borne diseases here in Ireland,” explained Dr Barrett.

Research has suggested that Schmallenberg reached the UK and Ireland when infected midges were carried on the wind from farms in France and Belgium.

“Midges can be blown up to about 400km,” said Dr Barrett. “There is obviously a greater concentration [of midges] within 20km or 30km but they can be blown up to 400km.”

Department of Agriculture surveillance on ‘sentinel’ farms shows that by the end of the 2016 midge season, the disease had spread into 22 out of 26 counties in Ireland.

All eyes on spread of new bluetongue strain

Ireland has been on high alert for a new strain of bluetongue virus since it first emerged in northern Europe last year.

Bluetongue symptoms include loss of appetite, milk yield drop, sores on the nose, gums and dental pads, swelling of the face, lips and tongue (ie “bluetongue”) and breathing difficulties if the tongue swells.

Bluetongue serovirus 3 (BTV3), for which there was no vaccine available until just recently, has caused mortality rates as a high as 70% in affected sheep in previously unaffected countries.

Wet summers lead to poor-quality silage, and this can impact on colostrum quality for calves and lambs, resulting in higher disease prevalence.

The threat level to Irish farms was raised considerably when BTV3 was confirmed in a cow in Kent, England last November.

Culling, movement restrictions and an import ban on British animals on to the island of Ireland were among the measures put in place to stave off any potential BTV3 infection here.

It was not clear at the time whether the BTV3 case was linked to midge infection or the movement of infected livestock. Since then, there have been 126 bluetongue cases in England on 73 farms in four counties of England.

Thankfully, no evidence has been found so far that the bluetongue virus is circulating in midges in Britain.

However, testing has shown that BTV3 is carried by the same midge species that lives in Ireland, and any threat to Ireland’s bluetongue-free status is treated seriously.

The Department of Agriculture and Met Éireann have a monitoring system in place for daily wind monitoring to assess the threat of midge-borne diseases coming from Europe and the UK.

Should Ireland ever be hit with bluetongue, it could have devastating economic consequences for our export trade of live animals, semen, eggs and embryos.

Epizootic haemorrhagic disease on the move

Like bluetongue and Schmallenberg, epizootic haemorrhagic disease (EHD) is spread by the same biting midges that live in Ireland.

A notifiable disease with associated trading restrictions, it causes fever, weakness and bleeding in the skin and internal tissues of affected species including sheep, cattle, goats, deer, alpacas and llamas.

There is no vaccine for EHD available in Europe. Dr Barrett warned that the recent spread of EHD has increased the potential for spread across mainland Europe, towards the UK and Ireland.

EHD was reported for the first time in Europe in November 2022, in Sardinia, Italy. Since then, it has been confirmed in Sicily, Spain and Portugal.

By September 2023, EHD was confirmed in France, initially in the Hautes-Pyrénées and Pyrénées-Atlantiques region, close to the Spanish border, and later spreading along France’s west coast in late 2023.

Climate change will increase disease pressure on Ireland's farms, Dr Damien Barrett has warned. \ Donal O'Leary

While Dr Barrett said the greatest risk for EHD entering Ireland comes from the import of an infected animal from a country where it is currently circulating, there is also the risk of infected midges spreading to Britain and Ireland on the wind currents.

Weather and disease: drought link to cow fertility, colostrum and TB

While climate change threatens to bring new and exotic diseases to these shores, it is already negatively impacting our farm animals in a more fundamental way, Dr Barrett pointed out.

“Summer droughts have a direct impact on cow fertility. Reduced feed intake reduced productivity [in terms of meat and milk], and reduced body condition score,” he said.

The opposite is also true.

Drought conditions force more frequent interactions between cattle and badgers, increasing the risk of TB spread.

“A wet summer can lead to poor-quality silage, and we’ve seen this impacting the following spring in terms of poor-quality colostrum for calves and lambs.

“You know the old adage that colostrum is liquid gold, so if the colostrum is poor, the calves get off to a bad start and we’ve seen in such circumstances that you’re going to see an awful lot more disease,” he warned.

Summer droughts have a direct impact on cow fertility, feed intake, milk production and body condition score. \ Donal O'Leary

Changing weather and climate patterns also force changes in the movement of wildlife and their interaction with domestic livestock and people.

The impact of drought on badger and cattle habits was highlighted by Dr Barrett.

Firstly, in drought conditions badgers are more likely to drink from farm water troughs and encounter cattle that way.

However, with lower grass covers in a drought, cattle are more likely to graze closer to the ditch and badger setts.

“That’s the point in which the badgers may toilet and they’re the areas of greatest risk for transmission of TB,” said Dr Barrett.

Dr Damien Barrett, senior superintending veterinary inspector with the Department of Agriculture (fourth from left).

Climate change will directly affect how Ireland’s farmers manage their land, as they have to adapt to warmer temperatures, more intense rain and more intense droughts.

However, changing weather patterns also bring with them a whole new set of disease pressures for livestock.

Warmer temperatures will see midge, mosquito and tick populations increase and some move here from mainland Europe.

Midges carry diseases to which Ireland’s cattle herds and sheep flocks are susceptible – Schmallenberg virus, bluetongue and epizootic haemorrhagic disease.

Intense droughts will bring livestock into closer contact with badgers potentially carrying TB, while wetter conditions will increase the risk of liver fluke and other diseases.

So, how long until all this comes to pass?

It’s already happening, according to Dr Damien Barrett, senior superintending veterinary inspector with the Department of Agriculture.

In recent years, liver fluke infection has increased 12-fold in certain EU member states, including Ireland. Some of this increase is connected to drug resistance among fluke, but warmer and wetter weather is helping the liver fluke’s host mud snail to thrive.

Dr Barrett, speaking on an Agricultural Science Association webinar, highlighted the increased regional spread of liver fluke disease on the island of Ireland.

Livers showing the effect of liver fluke infection. From left: a healthy liver, a liver containing acute liver fluke; a chronically infected liver and a liver badly affected on and off for a long period of time.

“It was previously a disease of the northwest and west but now it’s actually moved more and more east,” he explained.

Lamb slaughter surveys show fluke antibodies recorded in Co Kilkenny, which would never have been the case 30 years ago.

“We have seen it move towards the southeast as rainfall increases,” he said.

Liver fluke disease costs the Irish agriculture industry an estimated €90m annually, according to Animal Health Ireland. Liver fluke disease can cut meat production by up to 20% in cattle and 30% in sheep and it can reduce milk output by 8% in cows.

The Ollerenshaw Summer Index 2023, predicted liver fluke infection being prevalent across all areas of Ireland except south Leinster.

Until recently, rumen fluke infection was not considered to be a significant parasitic disease in cattle or sheep. However, there has been an increase in outbreaks of scour and ill-thrift due to rumen fluke in certain years.

Rumen fluke, pictured, is associated with summers and autumns with high rainfall and is in the rise in Ireland.

“We’ve seen it become more and more prevalent as rainfall increases, particularly flooding events,” explained Dr Barrett. Submergence in water is an important part of the rumen fluke life cycle, and its rising incidence is linked to high levels of rainfall and more flooding.

“[Rumen fluke], over the last 20 years, has assumed a greater importance and it has a big impact on the thrive of cattle and sheep.”

Barber’s Pole worm: fatalities on 70 farms

The parasite haemonchus contortus, also known as the Barber’s Pole worm because of its red and white appearance, was almost unknown in Ireland 30 years ago. However, it began to emerge as a problem in the early 2000s and last year it surged to cause animal deaths on at least 70 farms.

“It first emerged in the south and southeast and now it has spread across the country,” Dr Barrett said.

Warmer temperatures will see midge, mosquito and tick populations increase, potentially carrying new diseases from mainland Europe. \ Donal O'Leary

Barber’s Pole larvae require warm, moist conditions to migrate to grass, conditions which will increase as climate patterns change in Ireland. See Figure 1.

Dr Barrett highlighted a link between changing weather patterns and the sudden emergence of certain worms in livestock.

“We often see surges in lungworms and stomach worms if we have a period of low rainfall, or almost drought, followed by high rainfall,” he explained.

The Ollerenshaw Summer Index 2023, predicted liver fluke infection being prevalent across all areas of Ireland except south Leinster.

“We’ve seen that to happen over the last few years from time to time, where you get… a lack of rain for several weeks, and then the rains come and there’s a surge in grass growth and there’s a surge in lungworm larvae and stomach worms, causing scour and other problems.”

Rising temperatures increase risk from vector-borne diseases such as Schmallenberg and bluetongue viruses carried by midges, and Lyme disease, carried by ticks.

Just as human health experts are warning that mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue-fever will spread into previously unaffected parts of northern Europe, Asia, North America and Australia, animal diseases will also move to new areas. Warmer and more humid weather, with fewer frosts and a shorter cold winter, will help midges, mosquitos and ticks thrive, increasing the risk of new and existing diseases.

Schmallenberg midges carried on wind

Schmallenberg virus emerged in Germany and the Netherlands in August 2011 when farmers and vets noted cattle and sheep with fever, lack of appetite, diarrhoea and reduced milk production.

A few months later, deformed lambs and calves were born on those same farms.

The young animals had deformed limbs, spinal curvature, twisted necks, shortened lower jaws and domed skulls.

Schmallenberg quickly spread all over Europe. It was discovered in Ireland in October 2012, following the birth of a deformed calf. That year, Schmallenberg infection was confirmed in a further 48 Irish cattle herds and 39 sheep flocks, predominantly in the southeast.

“That was the first time we’ve seen midge-borne diseases here in Ireland,” explained Dr Barrett.

Research has suggested that Schmallenberg reached the UK and Ireland when infected midges were carried on the wind from farms in France and Belgium.

“Midges can be blown up to about 400km,” said Dr Barrett. “There is obviously a greater concentration [of midges] within 20km or 30km but they can be blown up to 400km.”

Department of Agriculture surveillance on ‘sentinel’ farms shows that by the end of the 2016 midge season, the disease had spread into 22 out of 26 counties in Ireland.

All eyes on spread of new bluetongue strain

Ireland has been on high alert for a new strain of bluetongue virus since it first emerged in northern Europe last year.

Bluetongue symptoms include loss of appetite, milk yield drop, sores on the nose, gums and dental pads, swelling of the face, lips and tongue (ie “bluetongue”) and breathing difficulties if the tongue swells.

Bluetongue serovirus 3 (BTV3), for which there was no vaccine available until just recently, has caused mortality rates as a high as 70% in affected sheep in previously unaffected countries.

Wet summers lead to poor-quality silage, and this can impact on colostrum quality for calves and lambs, resulting in higher disease prevalence.

The threat level to Irish farms was raised considerably when BTV3 was confirmed in a cow in Kent, England last November.

Culling, movement restrictions and an import ban on British animals on to the island of Ireland were among the measures put in place to stave off any potential BTV3 infection here.

It was not clear at the time whether the BTV3 case was linked to midge infection or the movement of infected livestock. Since then, there have been 126 bluetongue cases in England on 73 farms in four counties of England.

Thankfully, no evidence has been found so far that the bluetongue virus is circulating in midges in Britain.

However, testing has shown that BTV3 is carried by the same midge species that lives in Ireland, and any threat to Ireland’s bluetongue-free status is treated seriously.

The Department of Agriculture and Met Éireann have a monitoring system in place for daily wind monitoring to assess the threat of midge-borne diseases coming from Europe and the UK.

Should Ireland ever be hit with bluetongue, it could have devastating economic consequences for our export trade of live animals, semen, eggs and embryos.

Epizootic haemorrhagic disease on the move

Like bluetongue and Schmallenberg, epizootic haemorrhagic disease (EHD) is spread by the same biting midges that live in Ireland.

A notifiable disease with associated trading restrictions, it causes fever, weakness and bleeding in the skin and internal tissues of affected species including sheep, cattle, goats, deer, alpacas and llamas.

There is no vaccine for EHD available in Europe. Dr Barrett warned that the recent spread of EHD has increased the potential for spread across mainland Europe, towards the UK and Ireland.

EHD was reported for the first time in Europe in November 2022, in Sardinia, Italy. Since then, it has been confirmed in Sicily, Spain and Portugal.

By September 2023, EHD was confirmed in France, initially in the Hautes-Pyrénées and Pyrénées-Atlantiques region, close to the Spanish border, and later spreading along France’s west coast in late 2023.

Climate change will increase disease pressure on Ireland's farms, Dr Damien Barrett has warned. \ Donal O'Leary

While Dr Barrett said the greatest risk for EHD entering Ireland comes from the import of an infected animal from a country where it is currently circulating, there is also the risk of infected midges spreading to Britain and Ireland on the wind currents.

Weather and disease: drought link to cow fertility, colostrum and TB

While climate change threatens to bring new and exotic diseases to these shores, it is already negatively impacting our farm animals in a more fundamental way, Dr Barrett pointed out.

“Summer droughts have a direct impact on cow fertility. Reduced feed intake reduced productivity [in terms of meat and milk], and reduced body condition score,” he said.

The opposite is also true.

Drought conditions force more frequent interactions between cattle and badgers, increasing the risk of TB spread.

“A wet summer can lead to poor-quality silage, and we’ve seen this impacting the following spring in terms of poor-quality colostrum for calves and lambs.

“You know the old adage that colostrum is liquid gold, so if the colostrum is poor, the calves get off to a bad start and we’ve seen in such circumstances that you’re going to see an awful lot more disease,” he warned.

Summer droughts have a direct impact on cow fertility, feed intake, milk production and body condition score. \ Donal O'Leary

Changing weather and climate patterns also force changes in the movement of wildlife and their interaction with domestic livestock and people.

The impact of drought on badger and cattle habits was highlighted by Dr Barrett.

Firstly, in drought conditions badgers are more likely to drink from farm water troughs and encounter cattle that way.

However, with lower grass covers in a drought, cattle are more likely to graze closer to the ditch and badger setts.

“That’s the point in which the badgers may toilet and they’re the areas of greatest risk for transmission of TB,” said Dr Barrett.

Dr Damien Barrett, senior superintending veterinary inspector with the Department of Agriculture (fourth from left).

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: