I recently had the pleasure of attending the first Biomethane Day Ireland conference in Dublin.

The event heard from industry experts on how biomethane systems and infrastructure have been developed in other European countries – often with considerably more success than what has been achieved in Ireland to date.

There was some disappointment among the attendees about the continued lack of clarity about the level of Government support which would be forthcoming to kickstart the industry here.

Alan Dillon, Minister of State at the Department of Climate, Energy and Environment, told the conference that the heads of bill for a major support mechanism would be published soon while also reiterating the Government target for “up to 5.7 terawatts of biomethane per annum”.

Much of the rest of the conference was taken up with presentations and discussions about overcoming the legal, planning, financial and technical challenges faced when attempting to develop a biomethane production plant in Ireland.

I came away from the conference less than optimistic about the future of the industry. There just seems to be so many challenges to overcome before production of gas from biomethane can get anywhere close to the Government target.

I met a friend of mine for dinner after the event and when they asked what the conference was about, I launched into a long-winded explanation of what anaerobic digestion is, why biomethane is important for Ireland’s environmental targets and how incredibly complex the system is from every perspective.

“Oh, we had one of them on my grandfather’s farm back home,” was my friend’s (very surprising) answer to my detailed introduction to what I presumed was a new idea.

My friend is from India, and for them there is nothing unusual or complex about making gas from manure. “My grandfather had about five buffalo. He’d take the manure and put in into the tank and there was a pipe coming out the top which fed gas directly into my grandmother’s stove where she used it for all the cooking.”

These comments took the wind out of my sails a little as I had been explaining something which I thought was cutting-edge, highly technical and innovative. For them it was old tech that was seen everywhere in rural India for generations.

I have since done a bit more research on the topic, and discovered that there are an estimated two million of these facilities currently in use in India. The biogas produced there is called “gobar gas” – gobar being the Hindi word for cow dung.

There is no significant complexity in the systems that are used in India. The fundamental design has been the same since at least the 1960s.

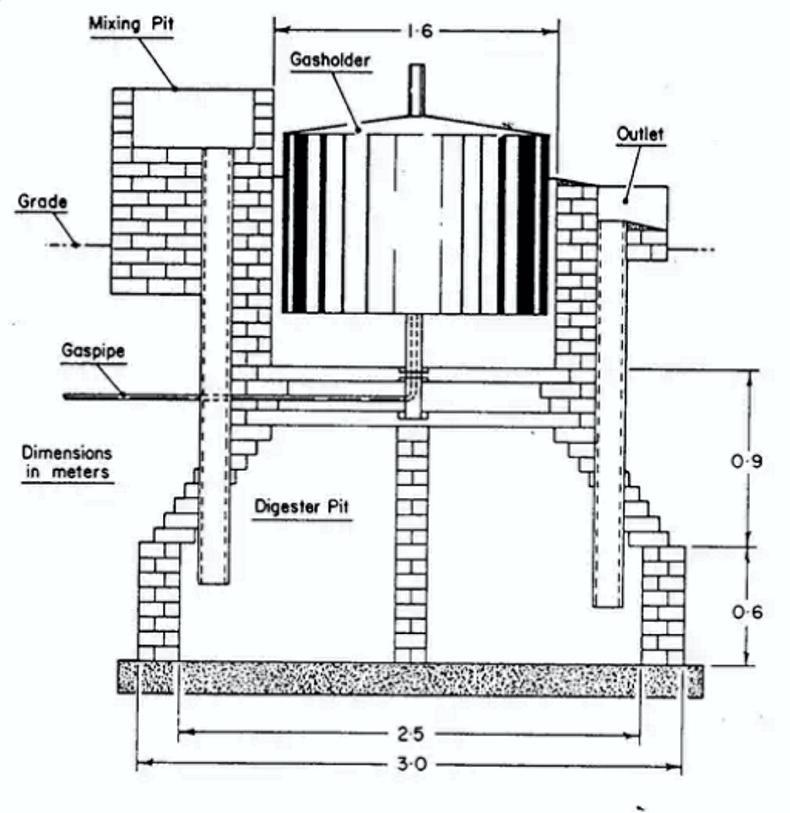

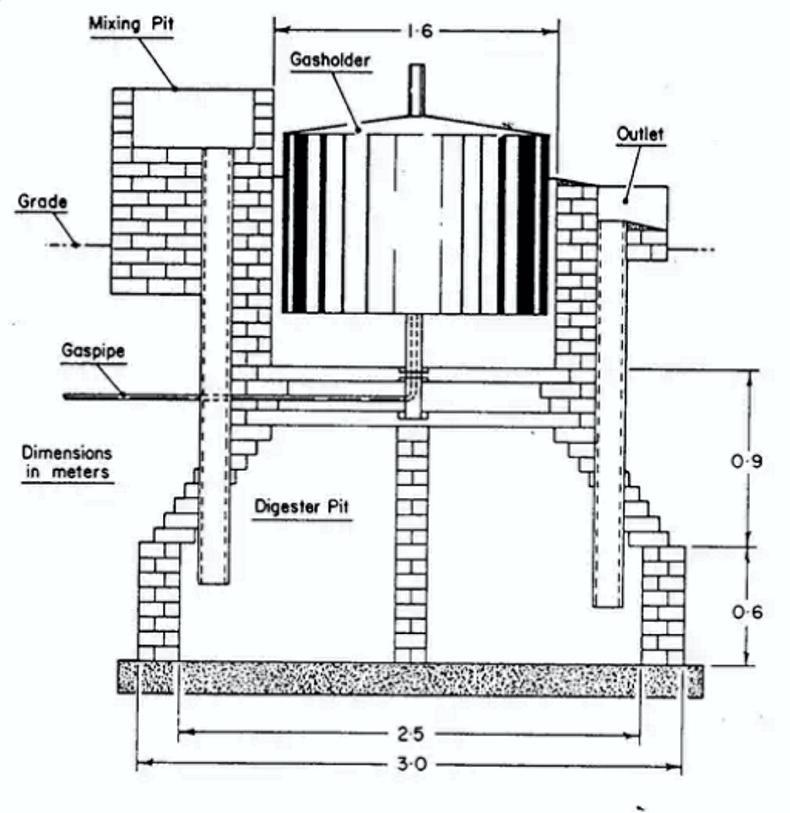

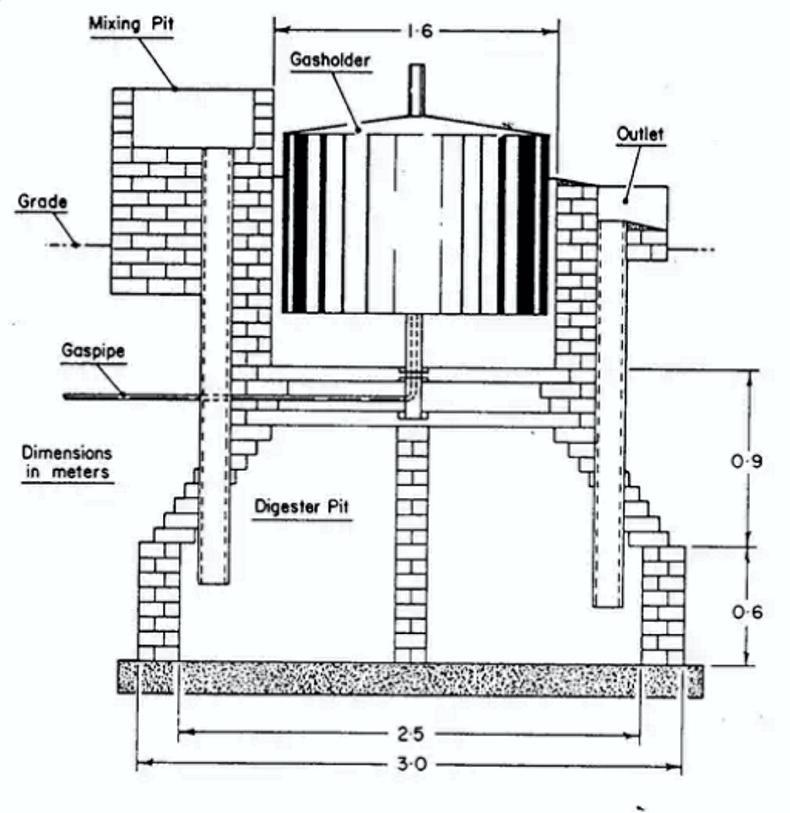

There is a small mixing tank where manure is combined with water which then feeds into the digestor.

The digestor itself is a round brick-linked tanked buried into the ground with a dividing wall which the slurry flows over as it is digested. The digestate then exits to another tank where it can be extracted for spreading on the land.

The tank is capped with a large steel collector which has an exit pipe for the gas. The steel cap, which floats on top of the slurry, is spun by hand for approximately 10 minutes every day to help agitate the mixture to improve gas production and reduce any chances of blockages in the system (see illustration 1 from a 1983 paper on Indian biogas production).

Cross section of gobar gas plant from "Biogas Systems in India - Robert Jon Lichtman (1983)".

India, and other countries in the region, have a natural advantage as the warmer temperatures there improve the efficiency of their systems, meaning there is no need for the tanks to be insulated to maintain optimum digestating warmth.

The thing that really stood out for me is how incredibly simple the process is. Beyond the hand-spun gas collector, there are no moving parts at all. Once the system is in place, it really is as easy as ‘slurry in, gas out’.

Getting back to the conference, it was obviously that the ambition for the industry in Ireland is to have large-scale operations which will feed biogas directly into the gas grid in the country. This adds many, many layers of complexity to what clearly is fundamentally a very simple process.

A large-scale anaerobic digestor needs planning permission, which seems to take years to be achieved, if it can be achieved at all. The environmental and legal hurdles are substantial too. The costs of connections to the gas grid can be eye-wateringly expensive, including the costs around installing a system to upgrade biogas to almost pure methane. Taking these challenges together, the cost of building a 40 GWh plant would be between €15m and €20m.

In India, a farm gobar gas facility can be built for under €2,000.

Comment

There are two trends worth focusing on in renewable developments in Ireland. First, much of the fundamental technology being relied on is both simple and well understood. Second, is the difficulty in establishing these energy sources due to a mixture of complex regulations, significant planning delays and considerable capital requirements.

Wind power generation, where Ireland has considerable advantages, has been around for centuries. True, the efficiency of modern systems is vastly higher than the picturesque Blennerville Windmill in Co Kerry. The biggest problem these days with wind technology is opposition to the siting for windfarms from groups concerned about visual impact.

Solar technology has also come on in leaps and bounds in recent years, but solar panels have existed since the mid-1800s. Concentrating the sun’s rays to create heat has been around since the invention of the magnifying glass. In Ireland, opposition to the proven technology seems to mostly come from the visual impact of large-scale installations.

For biomethane, the ambition to build grid-scale projects is laudable, but it seems to have managed to concentrate all the problems of both solar and wind by having what seems like the most vocal opposition groups while also having some of the highest regulatory hurdles to clear.

However, a farm scale system, where the biogas produced could be used on site for heating purposes – cutting out all the expense of grid connections – would be relatively cheap to install.

As the systems are generally built into the ground, there is would be no visual impact, so there should be nothing for opposition groups to complain about.

The decision of the Government here to concentrate on support for grid-scale anaerobic digestors seems short-sighted if it ignores the possibility of developing farm-scale operations.

After all, as with wind and solar, the actual technology is incredibly simple. It is only the paperwork that makes it so costly and complex.

I recently had the pleasure of attending the first Biomethane Day Ireland conference in Dublin.

The event heard from industry experts on how biomethane systems and infrastructure have been developed in other European countries – often with considerably more success than what has been achieved in Ireland to date.

There was some disappointment among the attendees about the continued lack of clarity about the level of Government support which would be forthcoming to kickstart the industry here.

Alan Dillon, Minister of State at the Department of Climate, Energy and Environment, told the conference that the heads of bill for a major support mechanism would be published soon while also reiterating the Government target for “up to 5.7 terawatts of biomethane per annum”.

Much of the rest of the conference was taken up with presentations and discussions about overcoming the legal, planning, financial and technical challenges faced when attempting to develop a biomethane production plant in Ireland.

I came away from the conference less than optimistic about the future of the industry. There just seems to be so many challenges to overcome before production of gas from biomethane can get anywhere close to the Government target.

I met a friend of mine for dinner after the event and when they asked what the conference was about, I launched into a long-winded explanation of what anaerobic digestion is, why biomethane is important for Ireland’s environmental targets and how incredibly complex the system is from every perspective.

“Oh, we had one of them on my grandfather’s farm back home,” was my friend’s (very surprising) answer to my detailed introduction to what I presumed was a new idea.

My friend is from India, and for them there is nothing unusual or complex about making gas from manure. “My grandfather had about five buffalo. He’d take the manure and put in into the tank and there was a pipe coming out the top which fed gas directly into my grandmother’s stove where she used it for all the cooking.”

These comments took the wind out of my sails a little as I had been explaining something which I thought was cutting-edge, highly technical and innovative. For them it was old tech that was seen everywhere in rural India for generations.

I have since done a bit more research on the topic, and discovered that there are an estimated two million of these facilities currently in use in India. The biogas produced there is called “gobar gas” – gobar being the Hindi word for cow dung.

There is no significant complexity in the systems that are used in India. The fundamental design has been the same since at least the 1960s.

There is a small mixing tank where manure is combined with water which then feeds into the digestor.

The digestor itself is a round brick-linked tanked buried into the ground with a dividing wall which the slurry flows over as it is digested. The digestate then exits to another tank where it can be extracted for spreading on the land.

The tank is capped with a large steel collector which has an exit pipe for the gas. The steel cap, which floats on top of the slurry, is spun by hand for approximately 10 minutes every day to help agitate the mixture to improve gas production and reduce any chances of blockages in the system (see illustration 1 from a 1983 paper on Indian biogas production).

Cross section of gobar gas plant from "Biogas Systems in India - Robert Jon Lichtman (1983)".

India, and other countries in the region, have a natural advantage as the warmer temperatures there improve the efficiency of their systems, meaning there is no need for the tanks to be insulated to maintain optimum digestating warmth.

The thing that really stood out for me is how incredibly simple the process is. Beyond the hand-spun gas collector, there are no moving parts at all. Once the system is in place, it really is as easy as ‘slurry in, gas out’.

Getting back to the conference, it was obviously that the ambition for the industry in Ireland is to have large-scale operations which will feed biogas directly into the gas grid in the country. This adds many, many layers of complexity to what clearly is fundamentally a very simple process.

A large-scale anaerobic digestor needs planning permission, which seems to take years to be achieved, if it can be achieved at all. The environmental and legal hurdles are substantial too. The costs of connections to the gas grid can be eye-wateringly expensive, including the costs around installing a system to upgrade biogas to almost pure methane. Taking these challenges together, the cost of building a 40 GWh plant would be between €15m and €20m.

In India, a farm gobar gas facility can be built for under €2,000.

Comment

There are two trends worth focusing on in renewable developments in Ireland. First, much of the fundamental technology being relied on is both simple and well understood. Second, is the difficulty in establishing these energy sources due to a mixture of complex regulations, significant planning delays and considerable capital requirements.

Wind power generation, where Ireland has considerable advantages, has been around for centuries. True, the efficiency of modern systems is vastly higher than the picturesque Blennerville Windmill in Co Kerry. The biggest problem these days with wind technology is opposition to the siting for windfarms from groups concerned about visual impact.

Solar technology has also come on in leaps and bounds in recent years, but solar panels have existed since the mid-1800s. Concentrating the sun’s rays to create heat has been around since the invention of the magnifying glass. In Ireland, opposition to the proven technology seems to mostly come from the visual impact of large-scale installations.

For biomethane, the ambition to build grid-scale projects is laudable, but it seems to have managed to concentrate all the problems of both solar and wind by having what seems like the most vocal opposition groups while also having some of the highest regulatory hurdles to clear.

However, a farm scale system, where the biogas produced could be used on site for heating purposes – cutting out all the expense of grid connections – would be relatively cheap to install.

As the systems are generally built into the ground, there is would be no visual impact, so there should be nothing for opposition groups to complain about.

The decision of the Government here to concentrate on support for grid-scale anaerobic digestors seems short-sighted if it ignores the possibility of developing farm-scale operations.

After all, as with wind and solar, the actual technology is incredibly simple. It is only the paperwork that makes it so costly and complex.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: