One of the four pillars of sustainability is financial sustainability and a key component of financial stability is cost competitiveness. Pigmeat exports are a key element of the Irish pig sector giving it a strong foundation of cost competitiveness and scale.

Feed is the largest single cost in pig production (~75%) and, therefore, has the biggest impact on competitiveness. However, a pig farm or country with very good KPIs may generate very high output, but this may not be achieved at the optimum economic efficiency.

A recent Teagasc Pig Feed Cost Competitiveness Report highlighted that Ireland, when compared to Denmark, Spain and the Netherlands, had a higher feed cost of 8c to 13c in feed cost per kg of pigmeat produced, when the feed cost per tonne was equalised.

Pigmeat is now a global commodity and Ireland exports a high percentage of its output (63%) on the International market. Therefore, an 8-13c/kg cost differential against our major international competitors places the Irish pig producer/sector at a significant competitive disadvantage.

One of the paths to reduce this differential is to improve Feed Conversion Efficiency (FCE) at farm level.

However, there are many factors affecting FCE, so which area should you target?

It’s important to quantify the potential FCE savings arising from some of the main factors and to rank these by potential impact.

Trial data

Using Teagasc research trial data and commercial on-farm case studies, data was modelled against the average national pig performance output (Teagasc Profit Monitor Report, 2023). The factors were then ranked numerically according to their impact on wean-sale feed conversion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Effect of selected factors on Wean-Sale FCE.

In this modelling, health and feeder type are shown to have the largest negative effect/highest ranking, and mortality/condemnations the lowest. However, the FCE deterioration for condemnations and mortality, of 0.02 and 0.015 respectively, is based on a per 1% change in the mortality/condemnation rate.

Therefore, a spike in the incidence of mortality for a period of time on your pig unit, could move mortality significantly up the rankings to one of the biggest factors that negatively affects the feed efficiency on your unit. In the interest of brevity, this article will address three factors which the authors believe are readily obtainable ‘low hanging FCE fruit’ (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Selected ‘low-hanging FCE’ factors.

Herd health

Of the eight factors listed above, herd health had the largest negative effect on FCE. Surveillance and performance data from the Teagasc PathSurvPig research project indicated a wean-sale FCE deterioration of 0.16 when negative swine influenza herds were compared to positive-vaccinating herds.

Herds that were positive and vaccinating for PRRS and Pneumonia (M.Hyo.) also showed a significant deterioration in FCE when compared to negative herds. The scale of the FCE deterioration will depend on the clinical stage/effects of the disease and the level of control.

In general, the FCE deterioration indicates that monitoring and controlling herd health, or ideally having a negative herd for these three diseases, will generate the greatest improvement in feed conversion.

Can your herd’s immunity be boosted by better colostrum intake and a flexible/responsive vaccination programme? Are all sows given pain relief medication at the end of farrowing to stimulate colostrum let-down, and do piglets get a colostrum suckle within six hours of birth? Could your piglets be pre-mixed into their post weaning batches in the two weeks prior to weaning, to reduce stress and aggression at weaning?

Vaccination programmes play a huge role in controlling these diseases, but these programmes need to be fine-tuned on a continuous basis, as infection levels can rise and fall.

Monitoring and controlling the herd health requires slaughter-line checks, PCR blood sampling and blood/saliva rope sampling at regular intervals throughout the year to obtain a continuous herd health profile, rather than just blood testing when a spike/outbreak occurs.

Being proactive rather than reactive helps to identify potential health problems. Active implementation of bio-check recommendations, especially for internal biosecurity, could also help to control/minimise disease transfer, this includes strict all-in and all-out.

Feed access

If pigs don’t have optimum access to feed, then their growth rates could decrease with a corresponding deterioration in feed efficiency. In recent years, the increase in the prolificacy of the Irish sow herd and higher finisher sale weights have resulted in pigs on some units having sub-optimum access to feed.

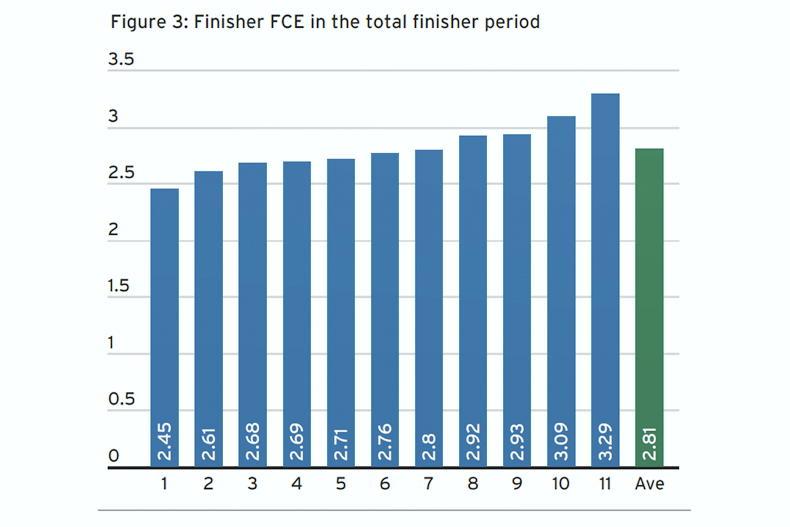

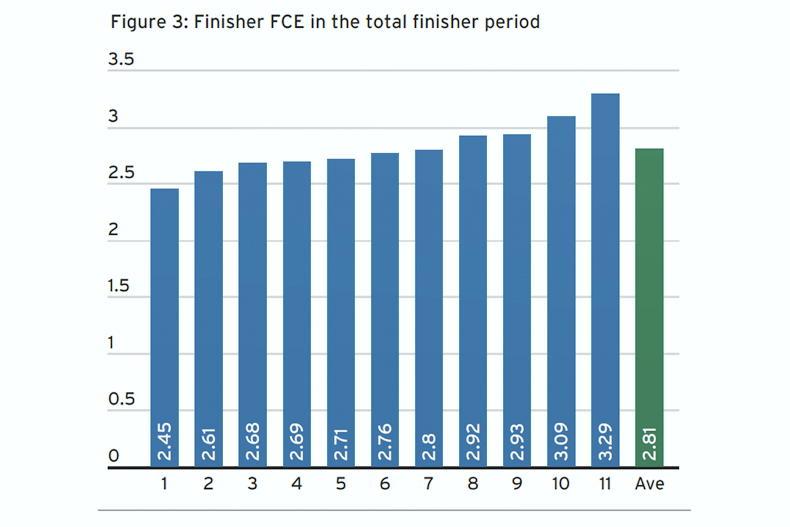

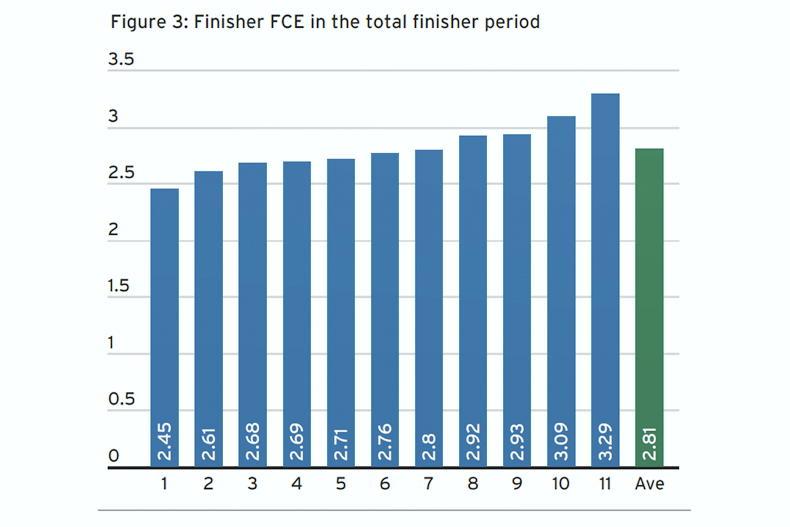

A recent case study on a commercial pig unit illustrated this point, with sub-optimum feed access leading to a deterioration in feed efficiency. The pig unit was an average size herd, with very good feed, housing and management, but a disappointing finisher feed efficiency of 2.81 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Finisher FCE in the total finisher period.

To pinpoint the issue on this pig unit, Michael, the finisher section manager, weighed pigs on-trial at the start of the finisher period, at the midpoint and the day prior to sale.

In addition, the feed dispensed through the wet feed valves was also recorded during this period. This illustrated that pigs performed well in the grower stage (FCE 2.3), but there was a performance decrease in the latter half of the finisher stage (FCE 3.24).

The latter period corresponded with the finisher pigs moving from grower feed to a lower specification finisher feed (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: FCE in the grower and finisher period respectively.

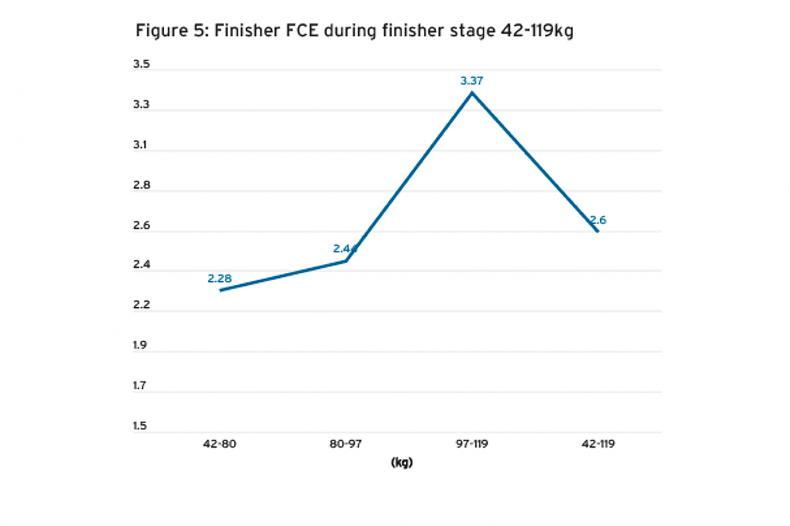

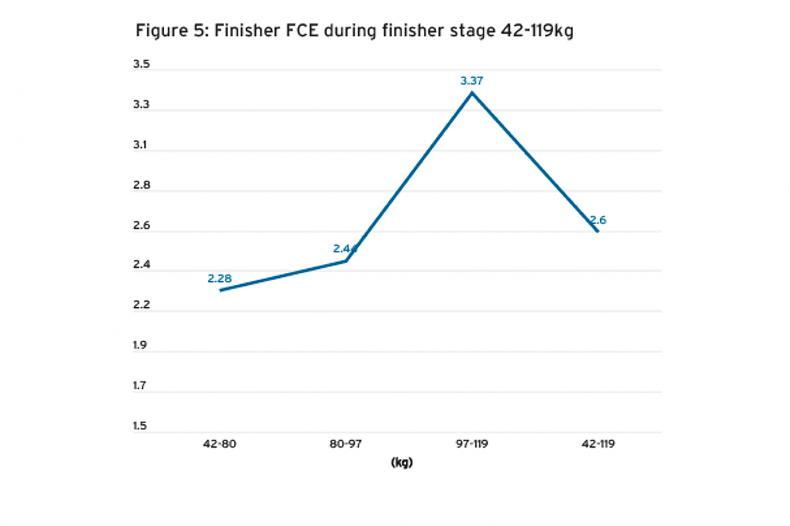

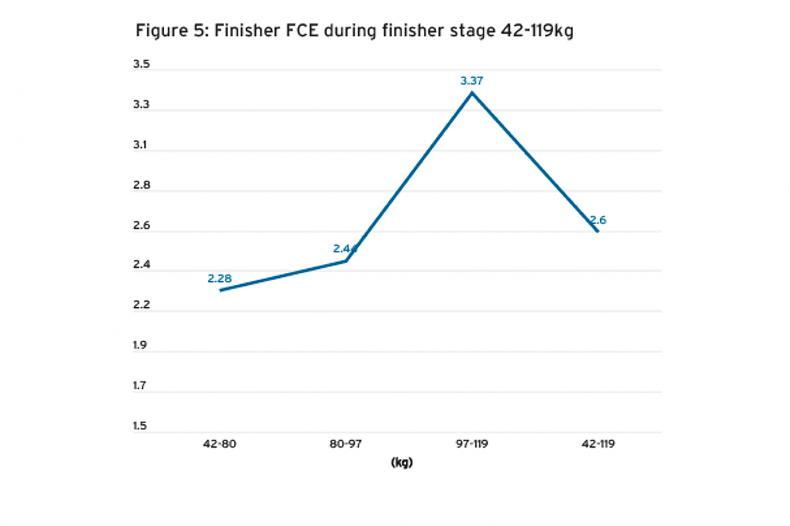

The blame was initially attributed to this finisher diet. However, in a subsequent trial when the pigs were kept on the grower diet for the total finisher period, the FCE was still poor in the latter stage. To obtain more data, the pigs were weighed more often and feed allowance per valve was recorded weekly. When the subsequent feed intake was allied to the growth data, this indicated a severe deterioration in FCE in the last three weeks prior to sale (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Finisher FCE during finisher stage 42-119kg.

It was determined that the reduction in feed intake, reduced performance and higher FCE, were due to sub-optimum feed trough access. Therefore, a second trial was undertaken in July and the number of pigs per pen was reduced by 15% on transfer into the finisher stage (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Comparison of April vs July finisher FCE trial.

This resulted in a dramatic improvement in feed intake, growth and FCE performance in the weeks prior to sale and improved the overall finisher FCE from 2.6 to 2.45. When this was translated into an overall wean-sale FCE, the improvement was 0.07.

The case study on this unit illustrated how important accurate data is when trying to improve FCE. Many units have access to this data, but may not be fully utilising it to resolve performance issues. It also demonstrates how a relatively small production change can save over €100,000 in feed costs on an annualised basis.

Mixing in finisher/split selling

We all know that mixing pens of pigs is not a good idea and should be avoided due to the associated fighting after mixing to establish their hierarchy or pecking order. However, some people don’t realise that reducing or splitting a pen of pigs has the same effect – fighting, reduced growth rate and a deterioration in FCE. When pigs are mixed on entry into the finisher stage, Moorepark trial work has demonstrated a finisher and weaning-sale FCE deterioration of 0.08 and 0.03 respectively. If these pigs were prior mixed on entry to second stage weaners, then the negative effect on FCE would have been even higher.

Any pig removed from a pen could cause the remaining pigs to establish a new pecking order and affect FCE, eg at transfer to finisher or prior to sale.

When the heaviest pigs, or tops, have to be taken from the pen to minimise the number of overweight pigs at sale, each time you remove a pig the remaining pigs must re-establish the pecking order. Each time this occurs it may probably cost a minimum of one day’s feed intake, approximately 2.8-3kg/pig. On some pig units, tops are taken from a pen on two different weeks before sale, which results in a waste of 6kg of feed for the remaining pigs and an increased risk of injury/tail biting. In addition, if tops are removed just a week before sale, the remaining pigs may only get the benefit of greater space allowance and feeder access for six days. Whereas if tops are removed three weeks prior to sale, then the remaining pigs get 20 days of benefit. Table 1 illustrates this problem very well. The trial compared pen performance when some tops were removed prior to sale at 20 days and 10 days.

In the first column, no tops were removed, in the second column two were removed at day 20 pre-sale and none after that. In the third to fifth columns, tops were removed at day 20 and day 10. The trial shows that the highest performance for the whole pen (total pen gain) was when tops were removed just once at three weeks (20 days) prior to sale. If you are selecting tops on your pig unit, then ‘do it once and do it right’ at three weeks pre-sale to reduce the negative effects on FCE. Never, ever, re-mix the pigs remaining in pens after the tops are removed, ie amalgamate the stragglers from a number of pens. In conclusion, there are many factors that affect your FCE, feed cost and competitiveness. To improve your FCE, assess the negative FCE factors that are pertinent to your unit, quantify the potential savings arising from each factor and then select which factors are the low-hanging FCE fruit that you can readily tackle.

One of the four pillars of sustainability is financial sustainability and a key component of financial stability is cost competitiveness. Pigmeat exports are a key element of the Irish pig sector giving it a strong foundation of cost competitiveness and scale.

Feed is the largest single cost in pig production (~75%) and, therefore, has the biggest impact on competitiveness. However, a pig farm or country with very good KPIs may generate very high output, but this may not be achieved at the optimum economic efficiency.

A recent Teagasc Pig Feed Cost Competitiveness Report highlighted that Ireland, when compared to Denmark, Spain and the Netherlands, had a higher feed cost of 8c to 13c in feed cost per kg of pigmeat produced, when the feed cost per tonne was equalised.

Pigmeat is now a global commodity and Ireland exports a high percentage of its output (63%) on the International market. Therefore, an 8-13c/kg cost differential against our major international competitors places the Irish pig producer/sector at a significant competitive disadvantage.

One of the paths to reduce this differential is to improve Feed Conversion Efficiency (FCE) at farm level.

However, there are many factors affecting FCE, so which area should you target?

It’s important to quantify the potential FCE savings arising from some of the main factors and to rank these by potential impact.

Trial data

Using Teagasc research trial data and commercial on-farm case studies, data was modelled against the average national pig performance output (Teagasc Profit Monitor Report, 2023). The factors were then ranked numerically according to their impact on wean-sale feed conversion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Effect of selected factors on Wean-Sale FCE.

In this modelling, health and feeder type are shown to have the largest negative effect/highest ranking, and mortality/condemnations the lowest. However, the FCE deterioration for condemnations and mortality, of 0.02 and 0.015 respectively, is based on a per 1% change in the mortality/condemnation rate.

Therefore, a spike in the incidence of mortality for a period of time on your pig unit, could move mortality significantly up the rankings to one of the biggest factors that negatively affects the feed efficiency on your unit. In the interest of brevity, this article will address three factors which the authors believe are readily obtainable ‘low hanging FCE fruit’ (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Selected ‘low-hanging FCE’ factors.

Herd health

Of the eight factors listed above, herd health had the largest negative effect on FCE. Surveillance and performance data from the Teagasc PathSurvPig research project indicated a wean-sale FCE deterioration of 0.16 when negative swine influenza herds were compared to positive-vaccinating herds.

Herds that were positive and vaccinating for PRRS and Pneumonia (M.Hyo.) also showed a significant deterioration in FCE when compared to negative herds. The scale of the FCE deterioration will depend on the clinical stage/effects of the disease and the level of control.

In general, the FCE deterioration indicates that monitoring and controlling herd health, or ideally having a negative herd for these three diseases, will generate the greatest improvement in feed conversion.

Can your herd’s immunity be boosted by better colostrum intake and a flexible/responsive vaccination programme? Are all sows given pain relief medication at the end of farrowing to stimulate colostrum let-down, and do piglets get a colostrum suckle within six hours of birth? Could your piglets be pre-mixed into their post weaning batches in the two weeks prior to weaning, to reduce stress and aggression at weaning?

Vaccination programmes play a huge role in controlling these diseases, but these programmes need to be fine-tuned on a continuous basis, as infection levels can rise and fall.

Monitoring and controlling the herd health requires slaughter-line checks, PCR blood sampling and blood/saliva rope sampling at regular intervals throughout the year to obtain a continuous herd health profile, rather than just blood testing when a spike/outbreak occurs.

Being proactive rather than reactive helps to identify potential health problems. Active implementation of bio-check recommendations, especially for internal biosecurity, could also help to control/minimise disease transfer, this includes strict all-in and all-out.

Feed access

If pigs don’t have optimum access to feed, then their growth rates could decrease with a corresponding deterioration in feed efficiency. In recent years, the increase in the prolificacy of the Irish sow herd and higher finisher sale weights have resulted in pigs on some units having sub-optimum access to feed.

A recent case study on a commercial pig unit illustrated this point, with sub-optimum feed access leading to a deterioration in feed efficiency. The pig unit was an average size herd, with very good feed, housing and management, but a disappointing finisher feed efficiency of 2.81 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Finisher FCE in the total finisher period.

To pinpoint the issue on this pig unit, Michael, the finisher section manager, weighed pigs on-trial at the start of the finisher period, at the midpoint and the day prior to sale.

In addition, the feed dispensed through the wet feed valves was also recorded during this period. This illustrated that pigs performed well in the grower stage (FCE 2.3), but there was a performance decrease in the latter half of the finisher stage (FCE 3.24).

The latter period corresponded with the finisher pigs moving from grower feed to a lower specification finisher feed (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: FCE in the grower and finisher period respectively.

The blame was initially attributed to this finisher diet. However, in a subsequent trial when the pigs were kept on the grower diet for the total finisher period, the FCE was still poor in the latter stage. To obtain more data, the pigs were weighed more often and feed allowance per valve was recorded weekly. When the subsequent feed intake was allied to the growth data, this indicated a severe deterioration in FCE in the last three weeks prior to sale (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Finisher FCE during finisher stage 42-119kg.

It was determined that the reduction in feed intake, reduced performance and higher FCE, were due to sub-optimum feed trough access. Therefore, a second trial was undertaken in July and the number of pigs per pen was reduced by 15% on transfer into the finisher stage (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Comparison of April vs July finisher FCE trial.

This resulted in a dramatic improvement in feed intake, growth and FCE performance in the weeks prior to sale and improved the overall finisher FCE from 2.6 to 2.45. When this was translated into an overall wean-sale FCE, the improvement was 0.07.

The case study on this unit illustrated how important accurate data is when trying to improve FCE. Many units have access to this data, but may not be fully utilising it to resolve performance issues. It also demonstrates how a relatively small production change can save over €100,000 in feed costs on an annualised basis.

Mixing in finisher/split selling

We all know that mixing pens of pigs is not a good idea and should be avoided due to the associated fighting after mixing to establish their hierarchy or pecking order. However, some people don’t realise that reducing or splitting a pen of pigs has the same effect – fighting, reduced growth rate and a deterioration in FCE. When pigs are mixed on entry into the finisher stage, Moorepark trial work has demonstrated a finisher and weaning-sale FCE deterioration of 0.08 and 0.03 respectively. If these pigs were prior mixed on entry to second stage weaners, then the negative effect on FCE would have been even higher.

Any pig removed from a pen could cause the remaining pigs to establish a new pecking order and affect FCE, eg at transfer to finisher or prior to sale.

When the heaviest pigs, or tops, have to be taken from the pen to minimise the number of overweight pigs at sale, each time you remove a pig the remaining pigs must re-establish the pecking order. Each time this occurs it may probably cost a minimum of one day’s feed intake, approximately 2.8-3kg/pig. On some pig units, tops are taken from a pen on two different weeks before sale, which results in a waste of 6kg of feed for the remaining pigs and an increased risk of injury/tail biting. In addition, if tops are removed just a week before sale, the remaining pigs may only get the benefit of greater space allowance and feeder access for six days. Whereas if tops are removed three weeks prior to sale, then the remaining pigs get 20 days of benefit. Table 1 illustrates this problem very well. The trial compared pen performance when some tops were removed prior to sale at 20 days and 10 days.

In the first column, no tops were removed, in the second column two were removed at day 20 pre-sale and none after that. In the third to fifth columns, tops were removed at day 20 and day 10. The trial shows that the highest performance for the whole pen (total pen gain) was when tops were removed just once at three weeks (20 days) prior to sale. If you are selecting tops on your pig unit, then ‘do it once and do it right’ at three weeks pre-sale to reduce the negative effects on FCE. Never, ever, re-mix the pigs remaining in pens after the tops are removed, ie amalgamate the stragglers from a number of pens. In conclusion, there are many factors that affect your FCE, feed cost and competitiveness. To improve your FCE, assess the negative FCE factors that are pertinent to your unit, quantify the potential savings arising from each factor and then select which factors are the low-hanging FCE fruit that you can readily tackle.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: